- Grass Pollen Allergy: First Vaccine Is Developed

- Flu May Be Spread Just By Breathing

- First Evidence of Sub-Saharan Africa Glassmaking

- Global Analysis Reveals How Sharks Travel the Oceans To Find Food

- First Global Atlas Of the Bacteria Living In Dirt

- Smokers Perceive Health Hazards of Smoking To Be Further In the Future vs. Non-Smokers

- Low Relationship Quality Is Linked To Higher BMI Among Women (But Not Men)

- How Treating Eczema Could Also Alleviate Asthma

- Breakthrough Study Shows How Plants Sense the World

- Radioactivity From Oil and Gas Wastewater Persists in Pennsylvania Stream Sediments

- People Who Sleep Less Than 8 Hours Are More Likely To Suffer From Depression, Anxiety

- When Is the Right Time To Start Infants On Solid Foods?

- Why Sitting In A Sauna May Be Good For Your Health

Dr. Patrick Seder is a post-doctoral researcher and instructor at the University of Virginia. His research focuses on well-being, positive emotions, culture, self-regulation, mindfulness...and the art of Andy Warhol.

Showing posts with label Nature. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nature. Show all posts

Fun (and Un-Fun) New Findings:

Labels:

Fun findings,

Nature,

RESEARCH

Switzerland Bans the Boiling Of Live Lobsters. Can They Really Feel Pain?

- The Swiss Federal Council issued an order this week banning cooks in Switzerland from placing live lobsters into pots of boiling water — joining a few other jurisdictions that have protections for the decapod crustaceans.

- Switzerland’s new measure stipulates that beginning March 1, lobsters must be knocked out — either by electric shock or “mechanical destruction” of the brain — before boiling them, according to Swiss public broadcaster RTS.

- The new order also states that lobsters, and other decapod crustaceans, can no longer be transported on ice or in ice water, but must be kept in the habitat they’re used to — saltwater.

- The announcement reignited a long-running debate: Can lobsters even feel pain?

- “They can sense their environment,” said Bob Bayer, executive director of the University of Maine’s Lobster Institute, “but they probably don’t have the ability to process pain.”

- A 2013 study in the Journal of Experimental Biology found that crabs avoided electric shocks, suggesting they can, in fact, feel pain. Bob Elwood, one of the study’s authors and a professor at Queen’s University Belfast, told BBC News at the time: “I don’t know what goes on in a crab’s mind. . . . But what I can say is the whole behavior goes beyond a straightforward reflex response and it fits all the criteria of pain.

- However, marine biologist Jeff Shields, a professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, said it’s unclear whether the reaction to negative stimuli is a pain response or simply an avoidance response. “That’s the problem,” he said, “there’s no way to tell.”

- But because lobsters do not have the neural pathways that mammals have and use in pain response, Shields said he does not believe lobsters feel pain.

- According to an explainer from the Lobster Institute, a research and educational organization, lobsters have a primitive nervous system, akin to an insect, such as a grasshopper. “Neither insects nor lobsters have brains,” according to the institute. “For an organism to perceive pain it must have a complex nervous system. Neurophysiologists tell us that lobsters, like insects, do not process pain.”

Learn more about this fascinating "debate" here.

Labels:

MODERN LIFE,

Nature

Modern Life: "What Happens to All the Salt We Dump On the Roads?"

It’s estimated that more than 22 million tons of salt are scattered on the roads of the U.S. annually...about 137 pounds of salt for every American.

But all that salt has to go somewhere.

After it dissolves--and is split into sodium and chloride ions--it gets carried away via runoff and deposited into both surface water (streams, lakes and rivers) and the groundwater under our feet.

Because it’s transported more easily than sodium, chloride is the greater concern, and in total, an estimated 40 percent of the country’s urban streams have chloride levels that exceed safe guidelines for aquatic life, largely because of road salt.

A range of studies has found that chloride from road salt can negatively impact the survival rates of crustaceans, amphibians such as salamanders and frogs, fish, plants and other organisms.

There’s even some evidence that it could hasten invasions of non-native plant species--in one marsh by the Massachusetts Turnpike, a study found that it aided the spread of salt-tolerant invasives.

Recently, in some areas, transportation departments have begun pursuing strategies to reduce salt use.

Salting before a storm, instead of after, can prevent snow and ice from binding to the asphalt, making the post-storm cleanup a little bit easier and allowing road crews to use less salt overall. Mixing the salt with slight amounts of water allows it to spread more, and blending in sand or gravel lets it to stick more easily and improve traction for cars.

Elsewhere, municipalities are trying out alternate de-icing compounds.

Over the past few years, beet juice, sugarcane molasses, and cheese brine, among other substances, have been mixed in with salt to reduce the overall chloride load on the environment. These don’t eliminate the need for conventional salt, but they could play a role in cutting down just how much we dump on the roads.

Read the full article (by Joseph Stromberg for Smithsonian) here.

Labels:

MODERN LIFE,

Nature

"The Man Who Revealed the Hidden Structure of Falling Snowflakes"

Read the full profile (by Owen Edwards) here. See the book here.

Beautiful, right?

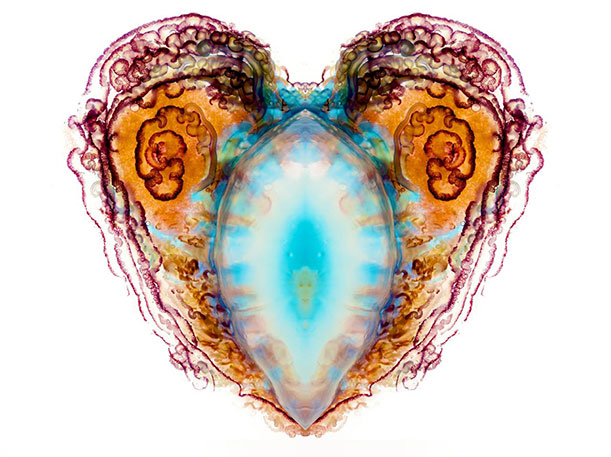

- A [Portuguese] man-of-war, if you’ve never encountered one, is a bit like a jellyfish. It is a transparent, gelatinous marine creature with stinging tentacles...

- Without their own means of locomotion, the little-studied men-of-war are at the whim of tides and currents.

- Scientists do not know how men-of-war breed or where their migrations take them because they cannot attach tracking devices to them, but, the animals wash up on shore in Florida from November to February. They turn from purple to deep reds the longer they are beached.

Learn more here and see more of Aaron Ansarov's striking photos here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)